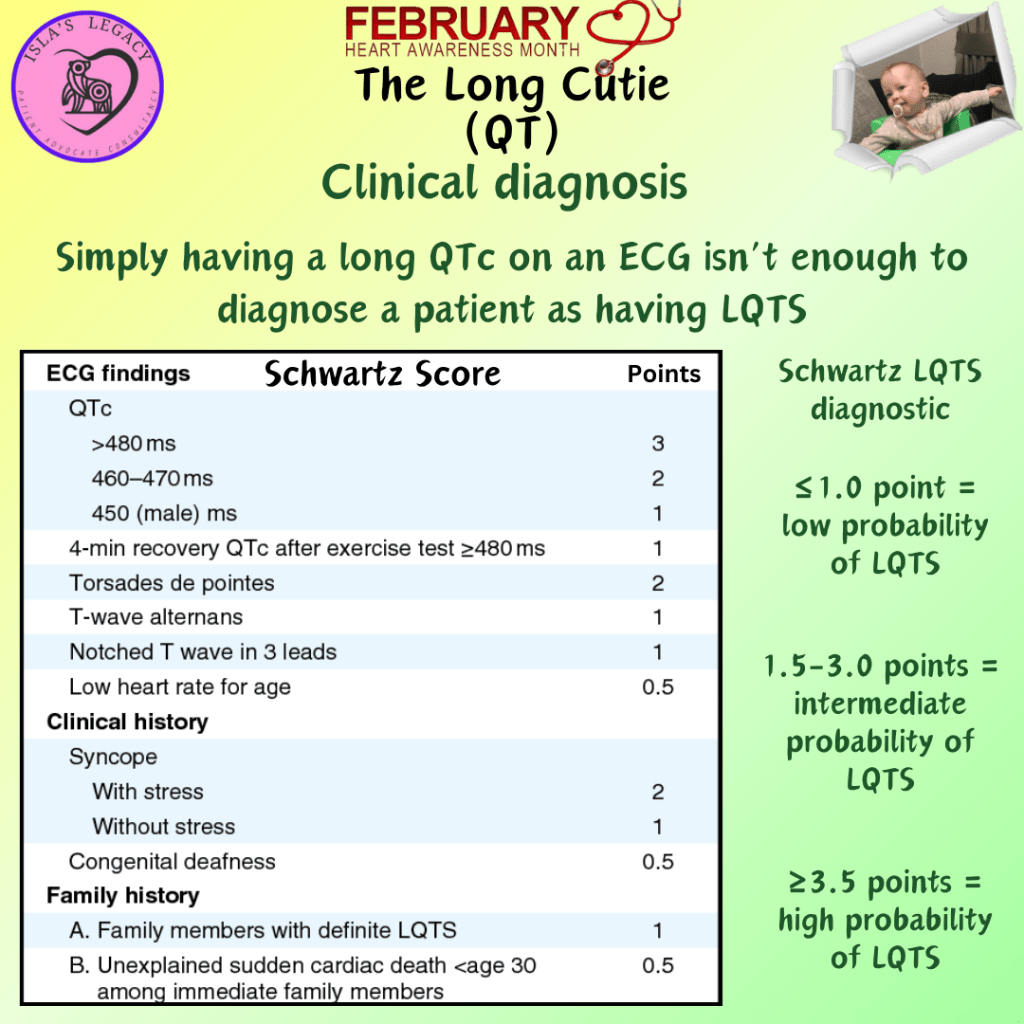

The actual diagnosis of Long QT Syndrome can’t come from a single ECG, so don’t let an ER or A&E doctor tell you you have Long QT from one visit. A Long QT diagnosis remains anchored to the LQTS diagnostic criteria score (also known as the ‘Schwartz-score’), which is an important tool for the initial clinical assessment of patients suspected of having LQTS. It is composed of ECG findings, clinical history, and family history. Importantly, ECG findings should be interpreted in the absence of QT-prolonging agents or other reversible causes.

LQTS is definitely diagnosed in the setting of a Schwartz-score ≥3.5, the presence of a pathogenic variant or repeated measures of QTc interval ≥500 ms in the absence of QT-prolonging drugs. An important consideration is that patients who are diagnosed with “acquired” Long QT Syndrome may in fact have underlying congenital LQTS that is unmasked with QT-prolonging drugs. In an international cohort of patients with apparent acquired LQTS, about a quarter of patients harboured a pathogenic LQTS gene variant. Therefore, patients with apparent acquired LQTS should always be evaluated after drug cessation.

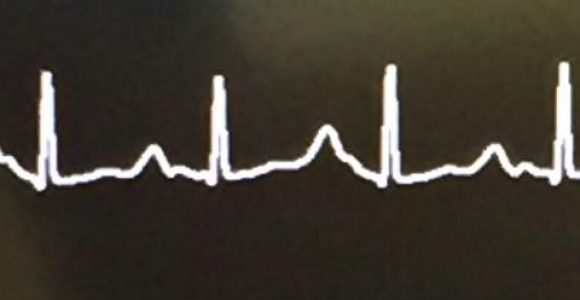

The foundations for the Schwartz-score was developed almost 30 years ago, before the identification of LQTS disease causing genes. Although this is utilised by doctors as a diagnostic tool, it is also a screening tool to determine which patients should be referred for genetic testing. Peter Schwartz has reiterated on numerous occasions, “I don’t measure the QT interval, I look at it.” The way the heart repolarises (T wave) can tell us a lot of information so it is important not to just look at the QT interval in isolation.