Long QT 3 is different to types 1 and 2 for a number of reasons: Firstly, it is a sodium channel malfunction rather than potassium. Secondly, it isn’t triggered by tachycardia but the QT actually prolongs at lower heart rates (bradycardia). Finally, it is a gain of function rather than a loss of function.

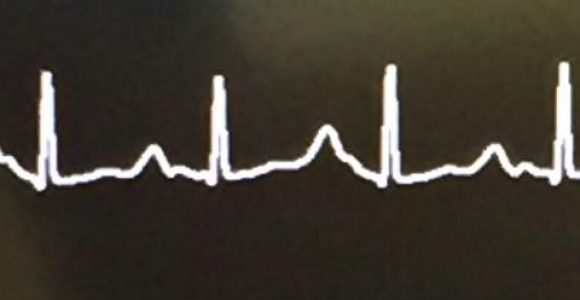

The ECG in LQTS3 usually shows a delayed, pointed T wave and allows clear observation of the ST segment prolongation.

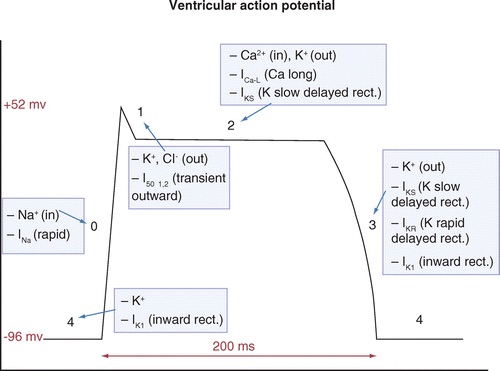

The affected gene in LQTS3 is SCN5A, which codes for the Nav1.5 sodium channel. Defective inactivation of the channel from Phase 0 allows sustained input of Na+ during phase 2 of the action potential, prolonging its duration (See picture 2). Current through this channel is commonly referred to as INa. The late current is due to failure of the channel to remain inactivated and hence enter a bursting mode in which significant current can enter when it should not. As the sodium channel is not adequately inactivated, the membrane remains slightly depolarised by the slow leaking of sodium into the cell. This leads to instability of the membrane, and early after-depolarisations.

LQT3 mutations are more lethal but less common.

There is still a lot of debate around the efficacy of beta blockers for Long QT 3 patients, with the most recent research (2023) suggesting that betas do not have any protective effect for SCN5A mutations. Sodium channel blockers are often recommended for LQT3 patients with Mexiletine or Flecainide actually reducing the QT interval significantly due to blocking the late surge of sodium caused by the channel improperly inactivating. These drugs however, especially Mexiletine, have numerous side effects which mean patient compliance with them long term is low. Hopefully soon there will be alternatives to these medications (@thryvtrx 👀).

As LQT3 is exacerbated by lower heart rates, pacemakers/ICDs are usually a good form of therapy as they prevent the QT stretching which occurs during sleep or rest.